By Matt Tracy and Shankar Ramakrishnan

(Reuters) -When President Donald Trump’s 90-day pause on U.S. tariffs ends Wednesday, once-bitten-twice-shy bond investors could take on more risk by adding high-yield bonds to portfolios, rather than panic-sell credit as seen after April 2’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariff announcement, said many fund managers and bankers.

Credit market shops as a whole are likely to avoid a knee-jerk reaction to sell the riskiest bonds in their portfolios, and instead buy them as they view any impasse on tariff negotiations as a way to a watered-down solution rather than a non-negotiable outcome, the fund managers and bankers said.

“Investors are likely to take any news of a tariff deadline extension in their stride and not overreact because there is always a put with this government – they will find some resolution to any impasse like they did post-Liberation Day,” said Sandeep Desai, co-head of North America leveraged debt capital markets at Deutsche Bank.

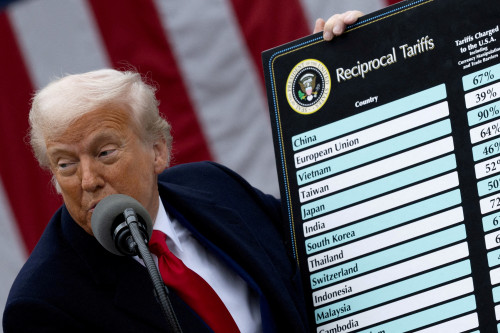

High-yield credit spreads, or the premium paid by companies over risk-free Treasuries, touched their widest levels in two years in the days after Liberation Day, when Trump announced wide-ranging tariffs on 57 countries.

Widening spreads mean an increase in borrowing costs and reflect market perceptions of a rise in default risk.

But this negativity did not last beyond a fortnight, and spreads are now a whopping 149 basis points (bps) inside those levels as of last week’s close, according to ICE BofA Global data..

On Wednesday, expectations of some sort of deal-making got a boost when Trump announced that the U.S. had struck a deal for a lower-than-promised 20% tariff on many Vietnamese exports.

A retracement in spreads showed credit investors were simply not worried that the macroeconomic impact of tariffs would lower the ability of a broad swathe of companies with the riskiest credit ratings to make interest payments on their debt.

The conviction in their fundamentals was so strong that even extreme geopolitical events – including an escalating war between Israel and Iran in late June – failed to push junk bond credit spreads or the default risk gauge wider.

“There definitely seems to be a lot of looking through the headlines and what would, in prior periods, have served as extreme sources of volatility,” said Michael Levitin, managing director and co-head of liquid credit at MidOcean Partners.

For Joseph Lynch, global head of non-investment-grade credit at Neuberger Berman, it was a case of investors appreciating the improved quality of the high-yield bond universe.

More debt has become secured by a certain amount of collateral, while more companies are using new deal proceeds to optimize their balance sheets rather than for leveraged buyouts, he said.

Over the past five years, the percentage has increased to nearly 35% from 20% of U.S. high-yield bonds secured by collateral like physical assets or even shares, noted Jennifer Haaz, investment specialist at Penn Mutual Asset Management, in a recent report. These had a higher recovery rate than those that were unsecured in case of a default, she added.

The extra security of collateral also helped companies reduce the cost of their debt, which investors viewed as a sign of more prudent balance sheet management by companies.

HUNT FOR YIELD

Junk-rated debt was also offering yields between 7% and 8%, which investors saw as more than compensating for any default risk when improved fundamentals were taken into account. This has increased demand, which has in turn created what bankers called a supply-demand imbalance and pressured spreads tighter.

U.S. high-yield funds saw outflows of $8.42 billion in April after Liberation Day, according to data from the London Stock Exchange Group. But since then the direction of flow has reversed with high-yield funds receiving roughly $13 billion of inflows between May 1 and June 25.

But only $149.8 billion in new U.S. junk bonds have been issued so far this year, versus more than $165.5 billion this time last year, according to JPMorgan research published last Friday.

“You have a situation where the supply of bonds is just not keeping up with the demand,” said Piers Ronan, head of debt capital markets at Truist Securities.

Spreads could widen slightly, if at all, come Wednesday. If they do, Berman’s Lynch said, “we could be allocating more capital to high-yield.”

(Reporting by Matt Tracy and Shankar RamakrishnanEditing by Nick Zieminski)