By Howard Schneider

Springfield, Ohio (Reuters) – Rose Joseph and Banal Oreus followed different paths from Haiti to this struggling Midwestern industrial city that suddenly finds itself at the center of the U.S. presidential race.

Joseph arrived in 2022 after landing in Florida two years earlier to escape violence in Haiti, journeying north on word of good job prospects. Oreus, after stops in Brazil, Portugal and Mexico over an eight-year stretch, was drawn to Springfield in 2023 by family and friends who had already found their way here.

“The first motivation was job and work opportunities,” Joseph, now an Amazon warehouse worker who also does seasonal tax preparation work, said in an interview weeks before Tuesday night’s presidential debate.

The arrival of Joseph, Oreus and as many as 15,000 other immigrants from Haiti over roughly the last three years has reshaped this city of 58,000, offering some promise of economic revival along with growing pains. It also has unwittingly thrust Springfield into the middle of a national conversation about immigration, the economy and race – with Republican candidate Donald Trump and his running mate JD Vance recirculating what local police and city officials say are false claims of crimes and atrocious acts being committed by Haitians.

After a half-century of decline, data show the rapid population rebound has had a notable impact in Springfield.

Enrollment in Medicaid and federal food assistance and welfare programs surged. So did rents and vehicle accidents, including a collision last year when a Haitian without a U.S. driver’s license drove into a school bus, killing 11-year-old Aiden Clark and injuring 26 other children.

The number of affordable housing vouchers fell as landlords moved to market-based rents that were rising in the face of higher demand, a blow to existing residents relying on them.

What didn’t happen, according to interviews with a dozen local, county and officials as well as city police data, was any general rise in violent or property crime. Wages didn’t collapse, but surged with a rising number of job openings in a labor market that remained tight until recently.

In early July, days before he was tapped to be Trump’s running mate, Vance read aloud a letter from Springfield officials as he quizzed Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell at a congressional hearing on whether immigration added to inflation by increasing housing costs, and whether a rising supply of new workers hurt others by holding down wages.

What was happening in Springfield was “a very real example of this particular concern, straight from the horse’s mouth,” Vance said.

Powell responded that those effects might be apparent in some places, but overall the rising labor supply in recent years had helped grow the economy and slow inflation. And in the long run, he said, the impact was “kind of neutral” because markets adapt.

More recently, Vance and other Republicans have amplified false claims aired by some residents at weekly city commission meetings. City commissioners in their public comments have pushed back, noting that the vast majority of Haitians are in the country legally and have a right to live where they choose.

Springfield police also responded forcefully: “There have been no credible reports or specific claims of pets being harmed, injured or abused by individuals within the immigrant community,” they said in a statement. “Additionally, there have been no verified instances of immigrants engaging in illegal activities such as squatting or littering in front of residents’ homes.”

Still, Trump aired those falsehoods including the baseless claim that immigrants are eating pets in his debate Tuesday night with his Democratic opponent, Vice President Kamala Harris.

The Biden White House earlier on Tuesday condemned the viral misinformation, saying such remarks sought to divide Americans through lies and was based on racism.

‘A ROCKY SEASON’

Data from Springfield’s experience of the last few years paints a nuanced picture of the impact of rapid population growth.

Local rents did increase at the third-fastest pace among cities from May 2022 through the end of 2023, rising at a 14.6% annualized pace, data from Zillow shows. But the market also appears to be normalizing: Rents this year have risen at a modest 3.2% pace, 68th fastest among 400 cities sampled.

Local wages were slow to take off during the post-pandemic job market reshuffling, data from Chmura Economics & Analytics’ JobsEQ shows. But through the years associated with rising Haitian immigration, wages grew at a more than 6% annual pace for more than two years, about twice as long as seen nationally.

As Powell suggested, the process may have run its course. With the national labor market also cooling, wage growth in Springfield is down to 1.1%, job openings remain strong but the pace of hiring has slowed, and the unemployment rate has started to rise – faster here than nationally.

Just how many Haitians have arrived here remains unclear. Estimated at as many as 20,000 in the letter Vance read to Powell, city officials have since cut that to between 12,000 and 15,000 based on driver’s license and state identification data.

It is still a jarring increase from around 3,500 in just a few years – too fast to be reflected yet in Census data and the equivalent of 1.6 million or so new arrivals to New York City.

There are growing pains – indeed outright tension – as a result, with sometimes ugly rhetoric at city commission open comment periods. A small group of white supremacists marched through town during a jazz festival in mid-August.

For many local civic and business leaders, however, the advantages of having more people to fill jobs, start businesses, and buy goods and services are not lost.

Bordered by farms in the Miami Valley and with deep roots in farm equipment and other manufacturing, Springfield was stung like many heartland towns by late-20th century industrial decline.

A growing population “could absolutely have a long-term benefit,” Springfield mayor Rob Rue said in an interview. “But we are in a rocky season…The most difficult thing for myself as mayor, the five city commissioners, and the city manager is to navigate ourselves through this.”

That includes cooling some local tempers while trying to find funds for extra police, fire and health workers, and French and Creole translators.

‘WE NEEDED A WORKFORCE’

A federal immigration parole program allowed about 205,000 Haitians into the country before it was suspended for review in August. Hundreds of thousands others are here under Temporary Protected Status granted to those from the poor and often violence-wracked island.

Recent and longstanding immigrants said family and social networks, word-of-mouth, and the quest for higher wages and lower living costs helped draw people to Springfield.

“My friend and I heard about Ohio and Indiana, that there were a lot of work opportunities, and we made a plan and came,” said Joseph, who also helps staff a local Haitian cultural center and has resumed studies toward a social work degree at Clark State Community College.

Joseph, who arrived on a tourist visa, has applied for asylum and remains here legally under TPS – a status that Trump sought to revoke during his presidency before being blocked by the courts. She rented a two-bedroom apartment on the open market that she shares with a friend.

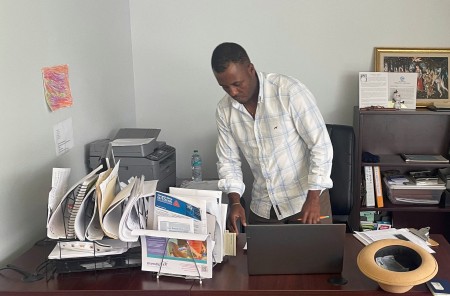

Oreus works full time at a local manufacturer and also at the St. Vincent De Paul Society, helping more recent arrivals prepare immigration, benefits, and work documents.

Why Springfield?

“I had friends here … My brother lived here, and I moved here to join him,” Oreus said amid the bustle of an afternoon legal clinic for new immigrants.

Springfield’s housing problems predate the Haitians’ arrival. A pair of studies by the Greater Ohio Policy Center found underinvestment and lack of code enforcement over the years, alongside population decline, left homes vacant and in disrepair.

There are some signs that is reversing.

A Ryan Homes subdivision on the outskirts of town, the first new home construction in years, is nearly built out and largely occupied. Another large development of higher-priced homes is underway, and a block of city-center town homes is sold out.

At a time when commercial real state is on shaky footing after the pandemic, one of several vacant downtown buildings is being converted to condominiums. And a boarded-up black structure towering over City Hall – briefly home to a failed bid to reincarnate the defunct E.F. Hutton investment firm brand – has attracted investor interest with a high-tech research hub as a possible anchor, one of several positive spillovers local development officials say they have seen from the Intel chip plant being built near Columbus.

For their part, city officials, local educators and the business community say that once the short-term disruptions are overcome, a growing population will add to a nascent revival.

“We needed a workforce,” to fill jobs in a resurgent local manufacturing sector and staff a growing number of warehouse and distribution centers, said Amy Donahoe, director of workforce development with the Greater Springfield Partnership. “They are coming in and they are working hard and they want to make money.”

(Reporting by Howard Schneider; Additional reporting by Ted Hesson in Washington; Editing by Dan Burns and Suzanne Goldenbertg)